The growing role of renewable electricity generation (RES-E) in countries around the globe goes along with essential changes in market dynamics, for example in terms of price levels and price volatilities. Correctly anticipating future developments of a country’s RES-E generation share is therefore crucial for all kinds of market stakeholders. This includes policy and regulators, generators, but also demand-side actors, whose best procurement and hedging strategies as well as opportunities to engage in evolving flexibility markets depend on the generation mix.

In the European Union (EU), countries have been committing to binding individual RES-E generation targets for more than a decade. In 2010, each Member State submitted to the EU its 2020 target for RES-E production shares as part of the country’s NREAP (National Renewable Energy Action Plan). These country-level plans were supposed to support the achievement of the common “20-20-20 by 2020” strategy (established in the context of the 2007 Climate and Energy Package) and its key goals, including GHG emissions, overall renewable energy shares, and energy efficiency. With the official final evaluation of the “20-20-20” targets coming up in 2022, this blog post presents a compact preview of expected national achievement levels and projected trajectories.

While official RES-E targets are often good first indicators of where countries are heading, they only tell a part of the story. It is therefore important to dig deeper into individual cases to answer the following questions: Are countries with ambitious trajectories likely to continue their paths? Are some countries – like the “hare” in Aesop’s fable – losing track, despite good potential and a promising start? Are there any “tortoises” whose rather moderate but constant pace can be expected to lead to the desired results after all?

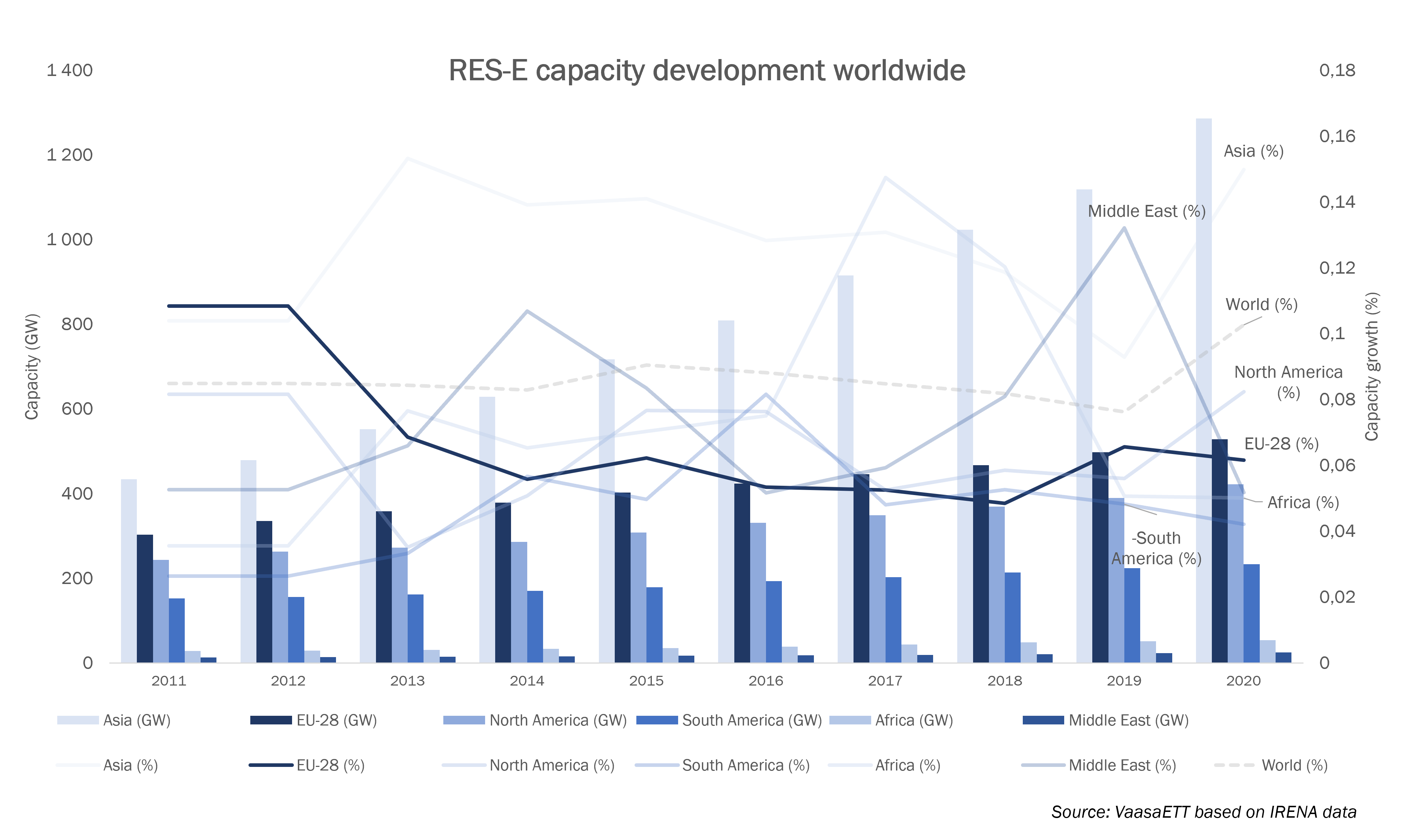

Looking at the EU as a whole, total RES-E capacity has been growing continuously over the past decade, as the following graph shows. Unlike in some other parts of the world, development has been fairly steady in recent years, with annual growth rates between 5% and 7% from 2013 to 2020.

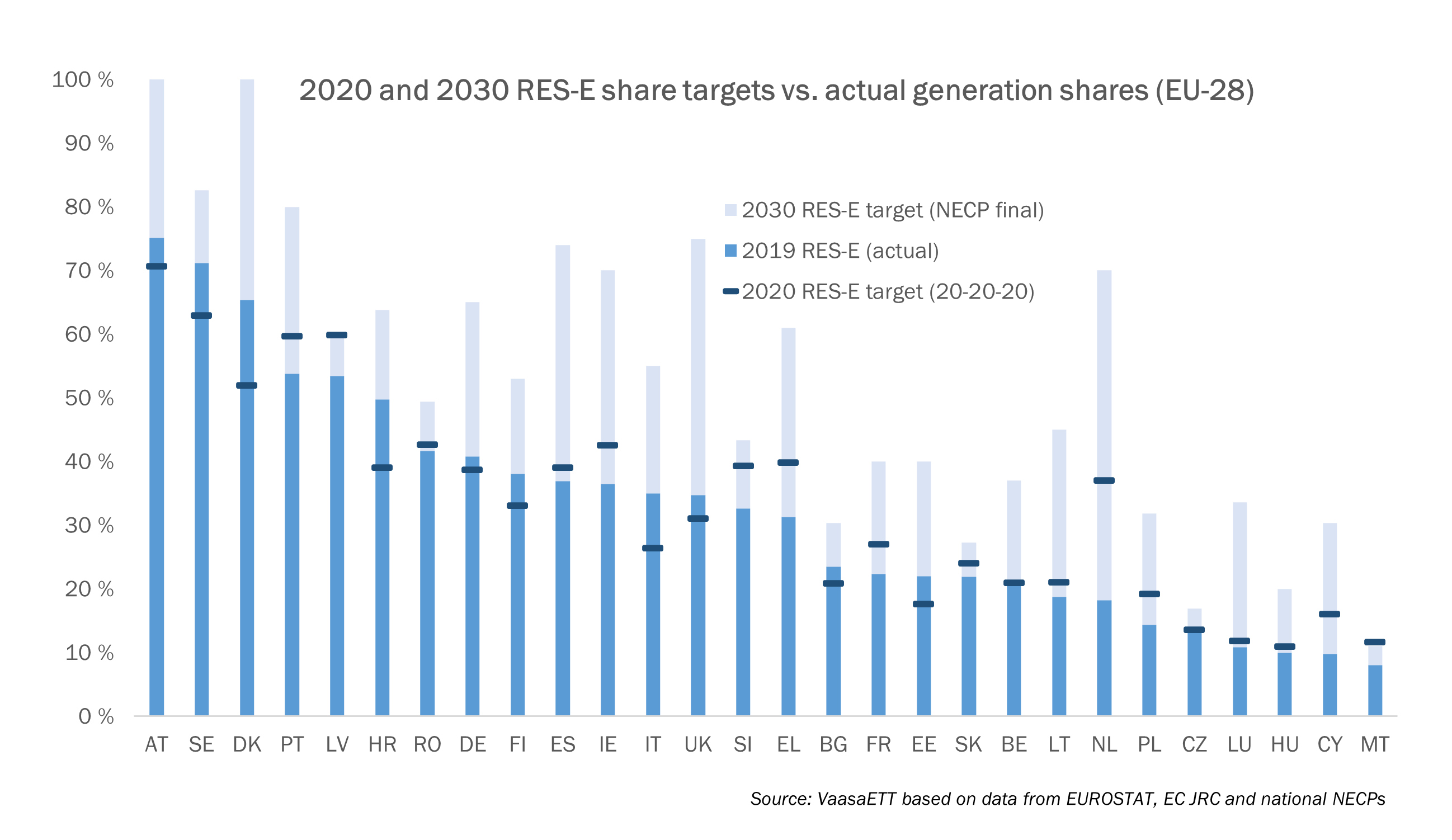

Zooming in to the country level, the past decade’s RES-E developments in Member States differ quite significantly from each other. But before getting into the weeds of comparing individual growth patterns, let us take a look at where countries currently stand in comparison to their past and future targets. For this purpose, the following figure combines three different values for each EU-28 country’s RES-E share (from here on always defined as percentages of domestic consumption):

- the above-mentioned 2020 RES-E targets as defined in the NREAPs

- the actual 2019 RES-E shares (as the most recent available values)

- the 2030 RES-E targets as defined in the NECPs (National Energy and Climate Plans, which had to be submitted to the EU in 2019)

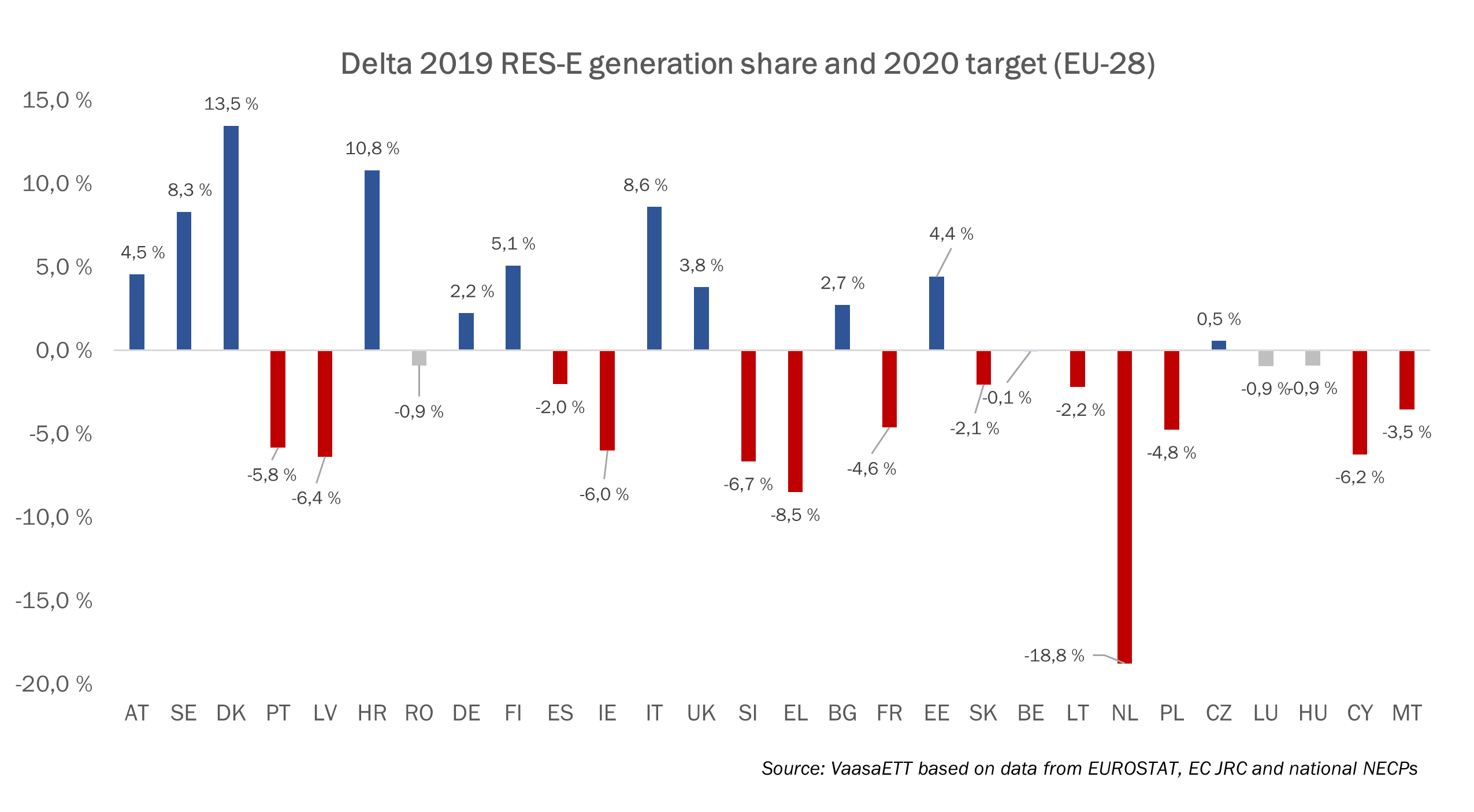

The figure reveals striking differences between the Member States in both ambitions and achievement levels: while some countries have set very high RES-E targets for themselves and had success in achieving them, others have generally low ambitions. Apart from that, there are countries with comparatively high ambitions on the one hand and significant achievement gaps on the other hand. This can be clearly seen in the following figure, which arranges the Member States according to the gaps between their realized 2019 RES-E generation shares and their 2020 targets (grey columns represent countries within a 1% distance of their targets).

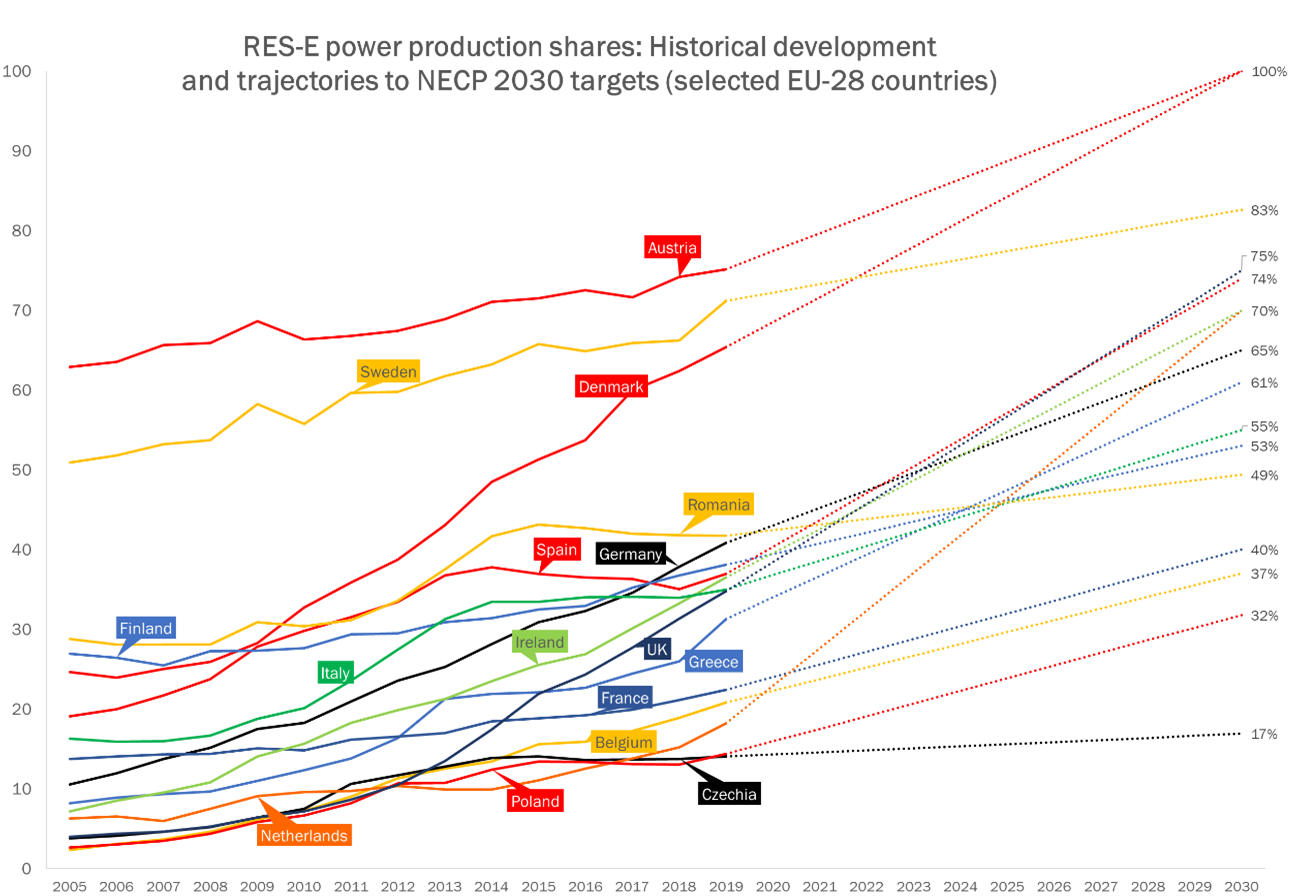

Two cases that stand out are the ones at the opposite ends of the spectrum: Denmark, which surpassed its own individual targets by the most, and the Netherlands, with the largest fulfillment gap by far. The following graph helps understand how the countries have arrived at these points, by plotting the development of RES-E shares in selected EU-28 countries between 2005 and 2019 (and the necessary trajectories to reach the individual 2030 targets):

In Denmark’s case, it is striking that development started from a rather moderate RES-E share in comparison to the other countries leading the field. The reason for this is that, unlike Austria and Sweden, Denmark could never rely on any significant hydropower capacity. Its steep “rise to glory” was initially built mainly on a very effective development of onshore wind projects, which in 2020 constituted 4.5 GW of the country’s 9.7 GW installed RES-E capacity. Having made use of nearly all appropriate onshore wind locations, the roles of solar PV (1.4 GW in 2020) and offshore wind (1.7 GW) have been growing. Regarding offshore wind, the current official expansion plans foresee the addition of 7.2 GW by 2030, but there are concrete discussions within the government to increase this number. Apart from intermittent RES-E, Denmark has increased its bioenergy capacity significantly in recent years (2.1 GW in 2020). This is connected to the ambition of decarbonizing the country’s heat supply system built around CHP and district heating. Moving forward in a determined and pragmatic way, Denmark can be expected to continue spearheading the green transformation of European energy systems and to provide showcases for electricity systems with increasing shares of intermittent RES-E.

Moving on across the North Sea to the Netherlands, concerns in view of the exceptionally large 2020 fulfillment gap of 18.8% might be intensified when looking at the steep trajectory needed to reach the 70% RES-E generation share target for 2030. However, recent developments give reason for some optimism. This is mainly due to the high volumes tendered via the Dutch “SDE+” mechanism in recent years (i.e., until 2019). Taking into account that the implementation of the granted projects takes its time, the 2020 RES-E capacity of 12.7 GW must be expected to more than double within the next few years. In that sense, the sharp turn towards the steep trajectory needed to reach the 2030 targets has in fact been initiated. On the other hand, the “SDE+” mechanism has been replaced in 2020 by the “SDE++” mechanism, in which RES-E projects compete against all kinds of other GHG mitigation measures, such as solutions to decarbonize heating or industrial processes. This makes the development of RES-E capacities less predictable. But then again, at least PV investors were successful in the first annual tender, securing 40% of the auctioned budget for the realization of projects with a total of 3.5 GW. Meanwhile, only 107 MW of onshore wind projects were successful. This suggests that market-driven financing models, such as corporate PPAs, could become even more important for this segment. Offshore wind projects fall under a separate regulatory regime anyway, with the ambition of adding 10.7 GW by 2030.

Taking a brief look at a couple of more countries, Spain might be a case where the comparison to Aesop’s “hare” might be somewhat appropriate. The sudden cancellation of the domestic support scheme in 2011 choked RES-E development that had previously looked very promising. During 2013 and 2018, annual growth rates were below 1%. However, the Spanish regulator has re-introduced effective RES-E instruments and the market has visibly started recovering in recent years. The current RES-E tender pipeline includes a total of 25 GW of new capacity by 2025.

Germany might be a market to which the “tortoise” attributes fit comparatively well: starting from a rather low RES-E share, development has been steady – although not at the same pace as Denmark. While this is not visible yet in the above graph, in recent years there have been significant problems regarding the development of onshore wind projects, leading to a long series of tenders not reaching their procurement goals. However, the new federal government, in power since autumn 2021, has committed to prioritizing the green energy transition. This includes, among other things, concrete measures to remove the problems in the onshore wind segment as well as a resolution to increase Germany’s 2030 RES-E target to 80%.

In general, it should be expected that many EU countries increase their 2030 RES-E targets until 2023, when updates of the NECPs are due. The revisions must take into account that the EU has increased its overarching 2030 renewables target to 40% with the adoption of the “Fit for ‘55” program in 2021. Larger leaps seem possible in the case of some eastern EU Member States that have long been skeptical about transitioning to RES-E. In combination with the drastic RES-E cost reductions over the past years, the recent increase in electricity wholesale market prices makes RES-E investments appear more economically viable than ever. With all the changes that are happening, it remains important for stakeholders to closely monitor the developments in their markets of interest.

0

0